I’m always a little daunted by the prospect of reading the classics. I don’t get on well with Charles Dickens or Thomas Hardy, though Jane Austen is my all time favourite writer. So I didn’t expect to be able to follow the writing of Charles Darwin when I first read On the Origin of Species. Amazingly, I could, and very easily. Darwin had not written a dense scientific treatise. It was a popular book intended for a very wide audience. It’s wonderfully poetic in places.

If you don’t believe me, I challenge you to read just the last chapter of the book, or even just the final paragraph if you’re that worried. The final chapter summarises the entire book, and the last paragraph is an even more succinct precis.

“It is interesting to contemplate a tangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent upon each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us. These laws, taken in the largest sense, being Growth with reproduction; Inheritance which is almost implied by reproduction; Variability from the indirect and direct action of the conditions of life, and from use and disuse; a Ratio of Increase so high as to lead to a Struggle for Life, and as a consequence to Natural Selection, entailing Divergence of Character and the Extinction of less improved forms. Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the higher animals, directly follows. There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone circling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being evolved.”

I used this paragraph as the basis for a few lessons work on non-fiction writing for a set of lessons The Charles Darwin Trust educational consultants (including me) wrote for the London Borough of Bromley. The borough had unsuccessfully attempted to get the natural environment around Down House listed as a World Heritage Site as it was there, in Darwin’s Landscape Laboratory, rather than the Galapagos Islands or anywhere in South America, that Darwin did most of his thinking, observation and experimentation that confirmed his ideas about natural selection.

I contrasted Darwin’s writing with that of modern science writers such as E.O. Wilson and Richard Dawkins (in hindsight I should have included some female science writers). I wanted to get across the idea to children that writing in science doesn’t have to be impenetrable and that by writing in an engaging and even poetic way, it can bring science to a wider audience.

Ewa put together a plan to run some teacher training on evolution in Yeovil Country Park, a wonderful setting, with their rangers. I went and co-delivered that recently. Along with Ewa’s book, a precis of Darwin’s life and work (which is often misunderstood) and the steps in his theory of evolution I demonstrated a number of possible activities teachers could do with children that Darwin himself did. I was pleased to note that several of the teachers had come across the blocks I wrote on

Ewa put together a plan to run some teacher training on evolution in Yeovil Country Park, a wonderful setting, with their rangers. I went and co-delivered that recently. Along with Ewa’s book, a precis of Darwin’s life and work (which is often misunderstood) and the steps in his theory of evolution I demonstrated a number of possible activities teachers could do with children that Darwin himself did. I was pleased to note that several of the teachers had come across the blocks I wrote on

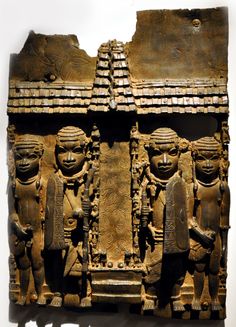

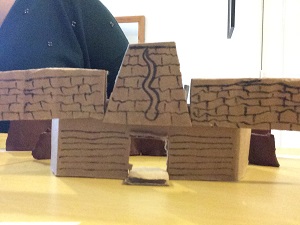

sources. Here’s my recreation of part of the Oba’s palace based on one of the Benin bronze plaques now in the British Museum below.

sources. Here’s my recreation of part of the Oba’s palace based on one of the Benin bronze plaques now in the British Museum below.